Independence, MO (IDP)

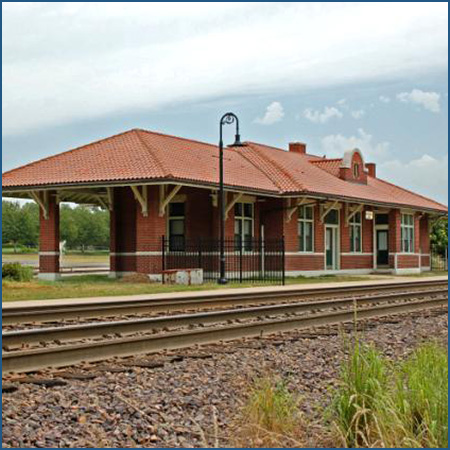

Commonly referred to as the “Truman Depot” in honor of its most famous customer - President Harry S. Truman - the red brick depot was built in 1913 for the Missouri Pacific Railroad.

600 South Grand Avenue

Independence, MO 64050-3564

Annual Station Ridership (FY 2023): 5,635

- Facility Ownership: City of Independence

- Parking Lot Ownership: Union Pacific Railroad, City of Independence

- Platform Ownership: Union Pacific Railroad

- Track Ownership: Union Pacific Railroad

Derrick James

Regional Contact

governmentaffairschi@amtrak.com

For information about Amtrak fares and schedules, please visit Amtrak.com or call 1-800-USA-RAIL (1-800-872-7245).

The Independence station is located southwest of the historic downtown. As a Senator, Vice President, and finally President of the United States, Harry S. Truman passed through the station hundreds of times while travelling between Independence and Washington, DC; therefore, the building is commonly referred to as the “Truman Depot.” To highlight 30 years of state-supported passenger rail service, Amtrak and the Missouri Department of Transportation sponsored a 2009 contest to rename the trains (formerly the Ann Rutledge and Missouri Mules) that link St. Louis and Kansas City via the picturesque towns and landscapes of the state’s interior. The winning entry—the Missouri River Runner—reflects the fact that the route often parallels the Missouri River, ending and beginning at riverfront cities.

The present station, built in 1913, sits between the main line tracks to the south and a branch line to the north. In the early 20th century, Mayor Llewellyn Jones strove to improve Independence’s public facilities. After four years of negotiations with the Missouri Pacific Railroad (MP), he convinced it to construct the new depot just west of its 1868 predecessor, which then became a freight house.

The one-story building rests upon a foundation capped by light grey limestone from which rise walls of dark red brick laid in common bond. Divided into three parts, the depot consists of a central projecting section with a broad hipped roof that is intersected by those of the smaller flanking wings. Covered in red Spanish tiles, the roof creates a deep eave supported by triangular brackets that encircles the structure and protects waiting passengers from inclement weather. Dormers capped by demi-lune parapets trimmed in limestone rise from the center of the street and trackside facades and provide visual interest as well as ventilation to the attic.

The central section originally sheltered the waiting room and a ticket/station manager’s office; these spaces received ample light from large windows with transoms set in pairs and triplets. On the exterior, each window is topped by a lintel while the sill is accented by a stringcourse which runs around the depot. Similar to the visible portion of the foundation, these details are executed in limestone for material continuity. A three-sided bay projecting onto the main line platform allowed the station master an unobstructed view down the tracks in order to monitor rail traffic.

The eastern wing contained the freight and express rooms as indicated by the wide sliding doors that accommodated the loading and offloading of large crates and parcels; the absence of windows discouraged theft and promoted an idea of security. The furthest portion of the western wing is an open air waiting area, a feature found in many of the stations built in the early twentieth century. Railroad heritage is reinforced by the red Missouri Pacific caboose on display next to the station; rail enthusiasts admire the MP logo painted on its side.

In 1971, the depot was closed to passenger traffic and became a freight building. A decade later, it was threatened with demolition due to lack of maintenance and continued deterioration. During this period, the wood platform around the building was removed, and a later photograph shows that many of the windows were boarded up. In order to bring attention to the structure, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979 for its architectural integrity and its associations with President Truman.

By the late 1980s, a group of civic minded residents, many of whom were interested in historic preservation, formed the “Friends of the Truman Depot” to raise money for a full restoration of the building. In 1995, amidst the campaign to increase awareness of the building’s importance to the history of Independence, an arson-set fire damaged the structure. With renewed energy, the friends group was able to gather sufficient funds to replace the roof with Spanish tile, which had been removed before 1940, and to open the former baggage room as a waiting room for rail passengers. The former waiting room has become the research library of the Jackson County Genealogical Society.

In 2008, Independence officials and the friends group announced plans for a comprehensive renovation of the building and ground. The city government’s Historic Preservation Division oversees the continuing work, which has included repairs to the tile roof, painting, interior plastering, the refurbishment of decorative planting beds, and numerous projects to prevent water infiltration such as adjustments to the gutters and downspouts and a re-grading of the land adjacent to the depot. Amtrak has assisted in the efforts by providing funds for a new outdoor bench and decorative trashcans that enhance the passenger experience.

The next phase of the project, planned for 2011, includes repairs to a sliding door and the refurbishing of the “Truman Depot” sign that was erected in front of the building to celebrate the President’s return to Independence in 1953. Money for all of the work—roughly $18,000—was provided from the Historic Preservation Division’s maintenance budget and donations submitted to a local foundation on behalf of the Friends of the Truman Depot. Much of the labor has been undertaken by volunteers, an indication of the value of the depot in the community.

When Europeans first visited this area of the Midwest, it was occupied by the Osage and Kansa American Indians who had moved west from the lower Ohio River Valley in the early seventeenth century. The two peoples shared many social and cultural characteristics and a common linguistic background descended from the Dhegian-Siouan family; intermarriage was common.

The American presence was not felt until the completion of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 which gave the young nation control over the immense territory drained by the Mississippi River. As the European-American population grew, its westward expansion in turn pushed tribes further west. The rich soils of Missouri attracted American settlers by the 1820s, and through a series of federal treaties between 1808 and 1825, the Osage and Kansa gave up their claims to much of the land in present day Missouri, Kansas, and Arkansas and were forced to locate on reservations.

In 1827, the town was established as the county seat of Jackson County, named for the great hero of the 1815 Battle of New Orleans who would later become president of the United States. It is said that “Independence” was chosen to reflect one of the general’s better known qualities. Many of the first settlers came from Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia. As in many frontier towns, law and order were quickly established—at least symbolically—through the construction of a log courthouse and jail. The two-room courthouse still stands south of Independence Square.

Three miles south of the Missouri River, the town site was located at the limit of water navigation, meaning that travelers had to obtain wagons and supplies to continue a journey overland. Independence benefitted as an endpoint of the new Santa Fe Trail connecting the Midwest with Santa Fe in northern Mexico.

News of gold and opportunity in California renewed Independence’s position as a trailhead. Gold seekers traveled by water to reach the city before preparing for the overland journey across the plains and the Rocky Mountains. Concurrent with development of the trail system to California was the opening up of the Northwest and the establishment of the Oregon Trail. Independence is the only town that was a starting point for all three of the commercial and migrant trails that carried more than 250,000 adventurers west from the 1830s to the 1850s.

Into this commotion arrived a group of Mormons in 1831 that was intent on the conversion of American Indians to their faith. Leader Joseph Smith declared Independence to be the site of “God’s City on Earth” and the community soon grew large as members traveled west from New York and Ohio. Smith encouraged his followers to purchase lots in the vicinity, and one was named as the future location of a holy temple. While the frontier settlement was tolerant of many people and actions, residents were wary of this plan to purchase large tracts of land. In addition, Missouri was a slave state, and the Mormons were against slavery. In 1833, the Mormons were driven out of town and would not return for another generation.

During the Civil War, Independence was twice captured by Confederate forces in 1862 and 1864; on the first night of the second battle, Confederate soldiers rested near the railroad right-of-way west of the current Amtrak station. The years of war left Independence in a perilous economic state. The trail trade had slowed to a trickle and the installation of new transportation connections—including the railroad—had been delayed. The Pacific Railroad obtained an 1849 charter for a rail line to run between St. Louis and a site in the western part of the state, with the aspiration of building to the Pacific Ocean. Ground was broken in St. Louis in 1851. Using rails, locomotives, and rolling stock shipped from England, the first five mile section of the road opened in 1852. Nine years later, the railroad reached Sedalia, within 80 miles of Independence, but the Civil War resulted in intermittent work on the line.

In 1864, construction began eastward from Kansas City, and the line to Independence opened in August. Similar to many fixed assets, the railroad was heavily damaged that fall during a Confederate raid led by Major General Sterling Price. He and his troops ravaged Pacific Railroad buildings, tracks, and rolling stock. The destruction was quickly assessed and repaired, and on September 19, 1865, the eastern and western sections of the railroad were joined; the first full run took 14 hours between Kansas City and St. Louis. In 1872, a reorganization of the railroad resulted in a name change to the better known Missouri Pacific Railway, and more than a century later it was subsumed into the Union Pacific Railroad.

Post-war, Independence began to rebuild, but it was soon overtaken by Kansas City which became the major regional power and an important railroad center. Independence was drawn into its sphere of influence and connected to it by new roads, railroads, and trolley lines. As the seat of county government, a solid prosperity did return and neighborhoods of comfortable homes rose on the outskirts of downtown. Manufacturing companies producing construction goods and machinery established a solid economic base.

In 1867, Mormon settlers under the leadership of Granville Hedrick returned to Independence with the goal of building the temple envisioned by Joseph Smith. After Smith’s death in 1844, Brigham Young had taken over the Church of Latter Day Saints and eventually led the majority of its followers to Utah. Church members such as Granville Hedrick did not believe Young to be Smith’s true successor, nor did they agree with all of Smith’s revelations.

Hedrick and his fellow believers worked to regain the property or “temple lot” that Smith had dedicated for the sacred building. Appropriately, the denomination became known as the Community of Christ (Temple Lot). After arguing with another denomination for control of the two-acre parcel, the Community of Christ finally received clear title to the land and in 1929 decided to begin construction of the building. The Great Depression started soon thereafter and the temple was never built. The site is today considered sacred by most Mormons, and many denominations have their own houses of worship in the immediate area although the Community of Christ (Temple Lot) views itself as the guardian of the temple site.

Independence’s most famous son, President Harry Truman, was actually born to the south in the farming community of Lamar in 1884. He became President of the United States in April 1945 upon the death of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, whose personality had defined the nation for the preceding 12 years. While shepherding the country after Roosevelt’s death, Truman was faced with the difficult decision to drop nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. His presidency witnessed the end of World War II and planning for the rebuilding of Europe, as well as the desegregation of the Army and the establishment of the United Nations.

Although Truman lived in Washington, D.C. while he was in national politics, Independence always remained home. Friends and admirers who waited at the MP depot to greet the President on a trip back to Missouri might have caught a glimpse of the Ferdinand Magellan, a Pullman car specially outfitted for Franklin Roosevelt and subsequently used by Truman and Eisenhower. The car was outfitted in the early 1940s with armor plate and bullet resistant glass, and had two escape hatches. President Truman used the car extensively during his 1948 “whistle-stop” tour as he sought reelection. Declared a National Historic Landmark in 1985, the Ferdinand Magellan is now in the collection of the Gold Coast Railroad Museum in Miami.

The Truman family house is now a National Historic Site administered by the National Park Service and many visitors to Independence drop by to learn about the 33rd President and his wife Bess. They are both buried at the nearby Truman Library and Museum where exhibits explore his time in office; researchers come to pour over the reams of personal documents that reveal his thought process on many of the important issues encountered during his years in public service.

The Missouri River Runner is financed primarily through funds made available by the Missouri Department of Transportation.

Station Building (with waiting room)

Features

- ATM not available

- No elevator

- No payphones

- No Quik-Trak kiosks

- No Restrooms

- Unaccompanied child travel not allowed

- No vending machines

- No WiFi

- Arrive at least 30 minutes prior to departure

Baggage

- Amtrak Express shipping not available

- No checked baggage service

- No checked baggage storage

- Bike boxes not available

- No baggage carts

- Ski bags not available

- No bag storage

- Shipping boxes not available

- No baggage assistance

Parking

- Same-day parking is available; fees may apply

- Overnight parking is available; fees may apply

Accessibility

- No payphones

- Accessible platform

- Accessible restrooms

- No accessible ticket office

- Accessible waiting room

- No accessible water fountain

- Same-day, accessible parking is available; fees may apply

- Overnight, accessible parking is available; fees may apply

- No high platform

- No wheelchair

- Wheelchair lift available

Hours

Station Waiting Room Hours

| Mon | 12:01 am - 11:59 pm |

| Tue | 12:01 am - 11:59 pm |

| Wed | 12:01 am - 11:59 pm |

| Thu | 12:01 am - 11:59 pm |

| Fri | 12:01 am - 11:59 pm |

| Sat | 12:01 am - 11:59 pm |

| Sun | 12:01 am - 11:59 pm |

Amtrak established the Great American Stations Project in 2006 to educate communities on the benefits of redeveloping train stations, offer tools to community leaders to preserve their stations, and provide the appropriate Amtrak resources.

Amtrak established the Great American Stations Project in 2006 to educate communities on the benefits of redeveloping train stations, offer tools to community leaders to preserve their stations, and provide the appropriate Amtrak resources. For more than 50 years, Amtrak has connected America and modernized train travel. Offering a safe, environmentally efficient way to reach more than 500 destinations across 46 states and parts of Canada, Amtrak provides travelers with an experience that sets a new standard. Book travel, check train status, access your eTicket and more through the

For more than 50 years, Amtrak has connected America and modernized train travel. Offering a safe, environmentally efficient way to reach more than 500 destinations across 46 states and parts of Canada, Amtrak provides travelers with an experience that sets a new standard. Book travel, check train status, access your eTicket and more through the